It’s been a mad few years – living through the pandemic then slowly emerging from a state of collective shell-shock feeling changed but unsure exactly how; the grotesque buffoon dethroned as leader of the free world, still loitering, still a threat; catastrophic bushfires on three continents on a scale humanity has never seen, interspersed with successive years of record rainfall and flooding; the familiar uneasiness of living in a society sliding heedlessly toward war with yet another demonised country. I had at times, during the pandemic especially, thought I should be documenting my experiences here. Life has been complicated. Social media platforms are too convenient and it’s easier to dump thoughts there, throwaways really, than to write a thoughtful and cohesive article.

The pandemic… where to begin? So much has and will be written about it. I think the best way I can contribute is to try and document my personal experiences and position them into broader social contexts.

Pandemic Year 1

At the end of 2019, I left the State Library of New South Wales where I’d been seconded for two years as Business Information Lead, responsible for the State Library’s own corporate records and archives and the related systems. I was proud to work there. I think most Sydneysiders and visitors would recognise the State Library as one of the city’s most loved institutions. The Mitchell Reading Room and the galleries around it are among our most beautiful public spaces, the Macquarie Building and its Marie Bashir Reading Room, Children’s Library, meeting rooms and computer services have a good claim to being our most useful, and the new auditorium under construction will multiply that.

I’d been on loan to the State Library from Fire and Rescue NSW, where I was returning with an informal agreement to work part time, giving me the time and brain-space to start my own business. After twenty-three years in Her Majesty’s service, I wanted to be my own boss, responsible for my own successes and failures instead of other people’s. In all those years in Government I felt I’d done very little of value to society. If I tried my hand in the world of business, perhaps I could achieve something worthwhile.

I reckoned I’d found a niche – mushroom varieties and complementary ingredients for Japanese cuisine. They’re tasty, nutritious, a fundamental in the diets of Australia’s large and expanding Asian demographic, and a growing number of consumers are looking for humane and sustainable sources of protein.

Two challenges surfaced, one that had always been a hindrance during my public service career and yet somehow still surprised every time, and another global one that blindsided everyone.

I came back to Fire and Rescue in a new role in corporate governance, working outside of IT for the first time in twenty-two years. My new boss, Bren Turner, supported my shift to working part-time. This apparently wasn’t supported by her boss, and instead became something we could talk about ‘down the track’. I had not only come back hoping to work part time, I went down a couple of pay grades, a compromise I was prepared to make for the flexibility to start my own business.

It soon became clear I’d transferred into a directorate with dysfunctional levels of tension and gloom, not atypical in the New South Wales public sector. These are often the result of personality clashes or a particular personality type in a position of power.

By March 2020 though, any angst I’d felt about the matter (actually only the latest chapter in a vocational despondency which had smoldered for two decades) dissipated. In November 2019, as I was farewelling the State Library to return to Fire and Rescue, it was already becoming apparent in Wuhan, a regional city in China, that a microscopic critter had begun its feast on humanity.

December or January, it’s a little blurry exactly when COVID-19 started pushing its way to the front of the news in our corner of the world, but around mid-March 2020 after it had begun ravaging Europe and North America, it quickly became the dominant topic. In those first months, COVID-19 had seemed yet another news item about a horrible virus inflicting unfortunate people in a distant part of the world, like we’d seen with SARS, MERS, Swine Flu, Avian Flu, Ebola… but in mid-March it was like flicking a switch. Life changed.

One small personal irony is that my director had just signed off on a flexible working agreement so I could spend a day a week working from home. It seems anachronistic now post-pandemic, but this was an arrangement Fire and Rescue made with some non-frontline headquarters staff if you could be bothered jumping through all the hoops. It required me to establish a workspace that conformed to WH&S requirements, provide photos and a floor plan with dimensions, draw up an emergency escape plan from my house, and write a case for working from home which was normally plagiarised between staff and referred to the need for “focused work time”, generally for the research and composition of documentation – policies, procedures, presentations, reports and stuff. The flexible working agreement had to be signed off by a number of senior staff.

Then, in mid-March 2020, Bren simply told her whole team to work from home. It was the first week I’d planned to spend Friday working at City of Sydney Fire Station under my new flexible work agreement. A week later the Commissioner followed and directed all non-frontline and non-trades staff to work from home. No workspace photos, emergency escape routes plotted onto floorplans, no business case required. Thus began an extraordinary couple of years in my working life, as it did for office workers in affluent societies around the world. It would reshape work hereafter in ways we are really still trying to understand.

Two technological advancements made it possible for people like me to work from home, and in a historical sense they seemed to arrive just in time. Firstly, after years of flakey internet service at my place, I hadn’t realised just how solid my connection had become after the upgrades under the National Broadband Network. Secondly, Microsoft had released Office 365 in 2016, and by 2020 it was ubiquitous. The “Zoom meeting” became part of the vernacular, though I seldom ever used that particular brand of online videoconferencing technology.

I’d been in the occasional video conference over the years using different technologies and it was in daily use at the ACCC during a stint I’d done with the Commonwealth in 2015. But overnight in March 2020, MS Teams became the venue for every meeting and every interaction with my work colleagues, as well as people throughout the public and private sectors I dealt with regularly. In 2018 and 2019 at the State Library, I’d laboured for months attempting to scribe the governance framework for the implementation of SharePoint which, in typical public sector fashion, had taken two years of work involving countless waffling meetings and design and policy rewrites to not implement. In the context of the pandemic, there was now no need to fuck around and bureaucratise the crap out of everything. Necessity was temporarily permitted to be the mother of invention, MS Teams was just there, and people stepped into it intuitively, without the need for months upon months upon years of hours of meetings to tease out and negotiate complicated frameworks for its use.

Soon after my return to Fire and Rescue, I’d found a ‘gap in the line’ within my new team. My new role was ostensibly to support internal performance audits, enterprise risk management, and compliance activities. However, some of my teammates were heavily invested and more comfortable with internal audits, so I landed primary responsibility for enterprise risk management, which in hindsight was such a fabulous opportunity.

Coincidentally, at the start of the pandemic, a major restructure of the Commissioner’s Office was announced and my directorate was to be carved up and redistributed into the new structure. It would take more than a year for that to unfold.

My little home office became my place of work five days a week. It just happened to be also my sleeping quarters, a situation that became unsustainable during the second year of the pandemic, contributing to a discomfort with life in general. But in 2020 it was part of the novelty and, curiously, of a new type of freedom. I look back on that first year of the pandemic with real nostalgia now.

As an office worker, I’d long hated the daily commute. It was a big part of why I left the State Library in 2019, and the Office of Environment and Heritage five years earlier. I’d struggle daily for a parking spot at the train station, only to squish into a ten thousand tonne sardine-can rolling station by station for anything between 48 minutes and three and a half hours into the city, to be corralled like cattle out into Wynyard Station and onto the streets to our offices. It was dehumanising, and it had consumed decades of my life and destroyed my soul. Working from home during the pandemic, there was none of that.

Yet, as I write in mid 2023 when things are back to some sort of a new normal, I dropped Chizuru off at the train station one morning this week and witnessed two separate instances of middle-aged men running with their cases and coats through the carpark to get to their train, with that earnest, pained expression on their faces that I know so well. Some days it’s the outward expression of the thought, “somebody just please put a bullet in my fucking head’.

Instead, during Pandemic year 1, I’d go for a walk in the morning, sometimes through the neighbourhood, sometimes in the bush. Every few hours throughout the workday, between meetings I’d jump on my bike and cycle up and down the street a few times to keep myself physically active and think through a question or compose a few lines of whatever document I was working on. Lunchtimes I’d go for another walk, spoilt by the bushland, a stream and even a waterfall only a few hundred metres from home.

With so many people staying close to their neighborhoods, new tracks I’d never seen before opened up as dozens of people like myself were getting out and exploring. I even conducted online meetings from bushland, sitting in a park or walking back from my mechanic. A lack of mobile phone coverage was the only thing that prevented me from conducting a meeting from the waterfall.

From early on we were conscious that work would probably be reshaped forever. We envisaged what has come to be known as the hybrid work environment, which recruiters now spruik in their job ads to attract staff. What we didn’t know is how long we’d be working full time at home, in a state of limbo, with social distancing and other restrictions to mitigate the spread of the virus which was on its way to killing millions. This was very isolating for some.

Each day, people would religiously check updates at the 11 AM briefing from Premier Gladys Berejiklian and Health Minister Brad Hazzard. We’d speculate over the numbers, find ourselves in deep discussion and analysis as we sliced and diced the figures from the Service NSW website – numbers infected, numbers of PCR tests done by local government area or postcode, numbers in ICU, per hospital, number of deaths. We braced ourselves for widespread tragedy.

We’d watched in horror at the news coming from Spain, then Italy, then the United Kingdom, and then the bewildering spectacle of a United States acutely divided, with an infantile President talking up hydroxychloroquine and speculating about injecting bleach into people’s bloodstream, as the number of dead in that country hit 160,000 then 300 thousand, five hundred, seven hundred thousand, and beyond a million.

As if this all wasn’t anxiety inducing enough, the pathological chatter from our political classes including all quarters of the media, of hatred and war with China, found ready ears in broader society.

The weirdness of social distancing was very off-putting at first – taking a wide berth around anyone you’d see on the street, poking elbows at each other instead of shaking hands. Wearing masks indoors was an adjustment. The contrast between city and country was stark during a visit to Port Macquarie in June 2020 for my mum’s birthday. Pulling into the carpark at Tacking Point Shopping Centre, Bryce and I automatically put on face masks before wandering in to grab a few things at the supermarket. In Sydney where rules were already tighter, if you were out and about you were wearing one, but at Tacking Point that day we may as well have been wearing burqas. Eyes were drawn to us. To my parochial hometown compatriots we were toxic aliens.

In New South Wales, measures were tweaked throughout 2020 and 2021, including a long period our movements were restricted to within our local government area or up to 10 km from home outside of it. For me that was Hornsby Shire and thousands of hectares of national parks and waterways, which felt like plenty. There were grounds for exemption, which importantly for Bryce included a partner/ companion outside your local area. His girlfriend at the time, Olivia Hannam, was just outside the 10 km in Wahroonga.

Some Sydney local government areas in the west and southwest had it worse, with a 5 km radius, night time curfews, and a heightened police presence enforcing compliance and handing out hefty fines. This opened the conservative government to accusations of political bias, with the subtext being divisions in class, race and income, made stark by imagery in the media of non-compliance going un-punished in the eastern suburbs.

Many were blindsided to learn that we live in a Federation. State borders were closed by Queensland and Western Australian, where parochial attitudes toward the heavily populated south-eastern states were exacerbated by the pandemic. Victoria, for a long time, closed the borders to residents of specific New South Wales post codes. Policy in relation to restrictions on travel, social distancing, work attendance, education, vaccination and other health matters varied from state to state and some people found this very unnatural. The media is so overawed by Commonwealth politics that Australians have become out of touch with the fact that most of the governing has occurred at the state level since before the Commonwealth existed, and the states are the fundamental jurisdiction of government and the Commonwealth is the add-on, not the other way around. The New South Wales public service is more than twice the size of the Commonwealth and the salaries higher.

Despite it all, through the fresh sunny autumn and mild winter, and into the spring and summer of 2020, looking back, every day and every season seemed idyllic.

In the evenings after work, I’d cycle up to a track off Alston Road leading to a beautiful lookout high above Berowra Waters and watch the sunset over the mountains. The half hour after sunset the sky is particularly beautiful, especially through winter. Sometimes I’d catch Claire, who’d been a fellow committee member for the Berowra RSL Youth Club. We’d sit and watch the sunset and chat. Claire raised three girls on her own while running a bookkeeping business that keeps her working long hours. She plays competitive volleyball alongside much younger teammates and opponents and devotes time to the admin of Volleyball NSW at the state level. She’s an SES volunteer and she’s been deployed throughout New South Wales during the natural disasters of recent years, and she plays cello.

With so many office workers at home rather than commuting to the city, some local businesses prospered. During much of the pandemic we weren’t able to dine out, but cafes and restaurants out in the suburbs became busy as locals dined in on takeaways or lined up outside their local cafes on workdays for their coffees, muffins and toasties rather than near the office in the city. The flip side is that the Sydney CBD spent many months deserted. Having spent much of my life working in the CBD, it was quite shocking on the few occasions I went in there during the pandemic. Still now there are empty shops down at the Martin Place end of the city. It’s been a long time since I saw that, perhaps never. Now and then I will hear of a cafe or restaurant, florist or other business that’s gone, including places I once frequented.

Except for a short period or in specific local government areas during COVID-19 outbreaks, tradespeople and others deemed essential workers weren’t subject to the same lockdown measures imposed on the rest of us. A shortage of tradespeople was an issue prior to the pandemic, but the pandemic exacerbated it, as households like mine took the opportunity to get some work done while we were home during the day. Without the expense of commuting, lunches, coffees, after-work drinks, holidays and entertainment, we were more cashed up too.

Prior to the pandemic, if I wanted any work done on my home I’d have to take time off work simply to get a quote, and if you wanted a second one it might be a month before you could be home for it. This was before you even took time off while the work was done. During the pandemic when people were home all the time, tradespeople were in high demand. We finally had a shoe cabinet and interior wall built, new balustrades and exterior staircase, a new kitchen, interior walls painted, fancy security screen doors, and a minor overhaul of the bathroom. Hereafter, for office workers, if you need to be home for any reason, you’ll just work from home.

In the meantime, strained relations between my superiors at work took its natural course. My boss Bren eventually left for a job elsewhere. Rather unusually, the Director above her (by all accounts a stress-monger and a bully) was eventually booted out. He’d snarled at a couple too many of the wrong people.

Heading into the second year of the Pandemic…

Bren had previously been in a job-share arrangement with another manager, who’d returned from maternity leave during 2020. ‘Returned’, it turned out, was an overstatement. For about a year this person was almost completely AWOL, assisted greatly by the new regime of working from home. When Bren moved on, any talk of working part-time was long forgotten by anyone but me, and work demands only grew as I was drawn into more senior positions. I began to realise I needed to quit completely if I was ever going to start a business. But I needed a secure income. Pandemic year 2 was not looking good.

I toyed with the idea of buying an established business that complemented my plans for mushrooms and Japanese cuisine and over the course of 2021 I enquired about several. Deep into the pandemic, grocery home delivery businesses in particular were taking off. I also looked at a catering supplies business and a few wholesale food distributors.

However, at the same time I was coaching Fire and Rescue leadership that by managing risk they are empowered to take it, I had a paralysingly low appetite for risk in my personal life. Over the years I’d seen too many small businesspeople lose everything – homes, businesses, marriages. The early ’90s recession hit many in my own family very hard, and my partner Chizuru is pessimistic by nature. No enquiries went beyond the initial information provided by business brokers under non-disclosure agreements.

The pandemic had come to Australia on the heels of the 2019-2020 Black Summer Bushfires, an energising time to be working at Fire and Rescue. I was analysing the risk implications arising out of the NSW Bushfire Inquiry, the Commonwealth Royal Commission into Natural Disaster Preparedness, Cheryl Steer’s exceptional review within my own agency, and the equivalent from the State Emergency Service. Enthusiastically, I did what I could to add value for the agency and the sector by initiating and contributing to conversation, opening new channels and discussions without the involvement, assent, or even acknowledgement of my barely present manager.

With reporting lines in flux due to our still undefined restructure, and with my manager AWOL, I may as well have been just going through the motions. Apart from some small early improvements to process, I could point to nothing I’d achieved in a year-and-a-half back at Fire and Rescue. In my 25 years in the public sector, this was the norm rather than the exception.

And thus, it would turn out to be again once my place in the new Commissioners Office structure was assigned under a different Director in June 2021.

Flood recovery on the Mid-North Coast

A year into the pandemic, the rains of 2021 flooded communities at record levels across a never-before-seen breadth of the state. Knowing how dispirited I’d become at Fire and Rescue, my friend Lang Ngo at the State Library brought my attention to a request for expressions of interest for temporary flood recovery staff with a new agency, Resilience NSW. Floods had devastated communities in the Hawkesbury-Nepean where I live, and on the rivers of the Mid-North Coast, including my old home town of Port Macquarie. I put my hand up and in one of her very last acts at Fire and Rescue, Bren Turner went out of her way to make it happen for me. I spent a month at the Flood Recovery Centre in Taree, followed by several months at Port Macquarie.

I landed in the Taree Flood Recovery Centre at the end of March 2021. If my first day would been anything to go by, I could actually be doing something worthwhile for a change, important work with tangible benefit to the public. Even more incredibly, on day one I’d been thrown the challenge of exercising some higher capabilities and really testing my potential, an opportunity which had never fallen my way in 25 years working in government.

The late afternoon autumn sunlight dappled under the trees and peacefully on the Manning River, beautiful despite showing scars of the trauma a couple of weeks earlier. I felt an intense mix of emotions as I walked out of the Flood Recovery Centre at the end of that first day heading to my motel – exhilarated by what had just happened and heartbroken at the decades of mismanagement and disempowerment. Heartbroken by the years spent untangling one complicated mess after another including hectic weeks you couldn’t get three consecutive minutes on any of them, that left you shell-shocked for a decade and numb forever after, and ironically through numbness, stronger and more resilient. By the scores of pointless tasks filed and forgotten, messed up and undone, the half-arsed coworkers and stuff-ups that had fallen to you and others to mop up. By the projects initiated and discontinued or never properly completed, that everyone patted each other on the back for anyway, the solutions looking for a problem you were told to force on people and the tens of millions of dollars you’d had a hand in flushing down the toilet.

Twenty-five years. I felt every minute and every sentence of it in that moment looking upon that beautiful river in this traumatised town. All the efforts, pain and stress, tense conversations, lost hours of sleep, anxious Sunday evenings, torturous train trips in to the office, all burned up on one whimsical exercise after another, consuming my life force. When I could have contributed so much. And there, finally, was proof. That day. The promise and hope in all those job applications written when my life measured only 25 years… another quarter of a century on it had all been for a net contribution to society of less than nothing.

an author making fun of tropes, if they do it well. Cervantes and Don Quixote comes to mind.

an author making fun of tropes, if they do it well. Cervantes and Don Quixote comes to mind.

brimmed cotton hat and gardening gloves impeccable despite the pile of leaves he and his buddy had amassed. ‘Kaba Kuneguchi’, he would write in my notebook, ‘September 30th, Heisei 23’ (2011), in hiragana to make it easy for the gaijin. I’d been circling the Miura Anjin memorial for ten minutes taking photos from outside the tall iron fence. Kaba was a volunteer with the Tsukuyama Park Preservation Society. Officialdom. It was okay.

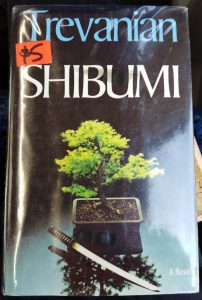

brimmed cotton hat and gardening gloves impeccable despite the pile of leaves he and his buddy had amassed. ‘Kaba Kuneguchi’, he would write in my notebook, ‘September 30th, Heisei 23’ (2011), in hiragana to make it easy for the gaijin. I’d been circling the Miura Anjin memorial for ten minutes taking photos from outside the tall iron fence. Kaba was a volunteer with the Tsukuyama Park Preservation Society. Officialdom. It was okay. Around that time, I read Trevanian’s Shibumi, a broad, brooding novel. Shibumi revealed to a fifteen-year-old that there are alternative frames through which to look at the world, and that all knowledge is refracted by the conduits through which it’s conveyed. The novel also introduced me to the excitement of the political thriller. Protagonist Nicolai Hel was born in Shanghai to an exiled White-Russian mother, and raised in Japan by a surrogate father, General Kishikawa of the Imperial Japanese Army. It’s this upbringing, with an acute sensitivity to custom, honour, the aesthetic, and clean, lethal violence, that would equip Nicolai for a career as an international assassin.

Around that time, I read Trevanian’s Shibumi, a broad, brooding novel. Shibumi revealed to a fifteen-year-old that there are alternative frames through which to look at the world, and that all knowledge is refracted by the conduits through which it’s conveyed. The novel also introduced me to the excitement of the political thriller. Protagonist Nicolai Hel was born in Shanghai to an exiled White-Russian mother, and raised in Japan by a surrogate father, General Kishikawa of the Imperial Japanese Army. It’s this upbringing, with an acute sensitivity to custom, honour, the aesthetic, and clean, lethal violence, that would equip Nicolai for a career as an international assassin. credited as the world’s first novel, and for her poetry and her diaries which provide a

credited as the world’s first novel, and for her poetry and her diaries which provide a into view, abstract forms in stone and yet full of humanity. One, with fluid edges and floral suggestions, was unmistakably feminine, the other, sharper edged with less organic accents, discernibly male. Here stood a man and woman in timeless consort. Side by side and full of vigour, the immigrant samurai and lady of Hemi overlooked their fief, and beyond it in the distance the metropolis once known as Edo. I’d stumbled across the mossy cenotaphs of Miura Anjin (William Adams) and Magome Oyuki. My guide map was in Japanese so I’d somehow not anticipated them, though I’d been following Adams’s trail. I wasn’t sure what I was looking for when I’d set out to find what I could of William Adams, but I knew this was it. Like Adams, and James Clavell’s John Blackthorne, I’d fallen in love with a Japanese. Like Adams and Blackthorne I’d fallen in love with the Japanese. In form and placement these

into view, abstract forms in stone and yet full of humanity. One, with fluid edges and floral suggestions, was unmistakably feminine, the other, sharper edged with less organic accents, discernibly male. Here stood a man and woman in timeless consort. Side by side and full of vigour, the immigrant samurai and lady of Hemi overlooked their fief, and beyond it in the distance the metropolis once known as Edo. I’d stumbled across the mossy cenotaphs of Miura Anjin (William Adams) and Magome Oyuki. My guide map was in Japanese so I’d somehow not anticipated them, though I’d been following Adams’s trail. I wasn’t sure what I was looking for when I’d set out to find what I could of William Adams, but I knew this was it. Like Adams, and James Clavell’s John Blackthorne, I’d fallen in love with a Japanese. Like Adams and Blackthorne I’d fallen in love with the Japanese. In form and placement these  cenotaphs eloquently captured Adams and

cenotaphs eloquently captured Adams and his benefactor, Tokugawa, in his retirement at Sunpu. Within Sunpu Castle Park survives a sprawling mandarin tree, planted by Ieyasu, that it’s easy to imagine could have borne fruit that Adams tasted.

his benefactor, Tokugawa, in his retirement at Sunpu. Within Sunpu Castle Park survives a sprawling mandarin tree, planted by Ieyasu, that it’s easy to imagine could have borne fruit that Adams tasted. sword) and its vicious application, are preoccupations in Western imagery of Japan. They coincide with the orientalist notion of the savage, inscrutable, deadly ‘other’. Some Japanese will chuckle at this Western preoccupation, and it marks one as a ‘hen-na-gaijin’ (silly foreigner). I must keep my curiosity about these things in the closet.

sword) and its vicious application, are preoccupations in Western imagery of Japan. They coincide with the orientalist notion of the savage, inscrutable, deadly ‘other’. Some Japanese will chuckle at this Western preoccupation, and it marks one as a ‘hen-na-gaijin’ (silly foreigner). I must keep my curiosity about these things in the closet. once, who was being a rogue, “She won’t say anything. She’ll just hand you the wakizashi,” (the short sword with which one performs seppuku).

once, who was being a rogue, “She won’t say anything. She’ll just hand you the wakizashi,” (the short sword with which one performs seppuku). on which they’d drifted wretchedly into Japanese waters, was Pieter Janszoon, her shipwright. In Shogun, Lord Toranaga has Blackthorne’s successfully constructed first ship destroyed, breaking his hopes of sailing home to England. Another trope: the wily, manipulative oriental.

on which they’d drifted wretchedly into Japanese waters, was Pieter Janszoon, her shipwright. In Shogun, Lord Toranaga has Blackthorne’s successfully constructed first ship destroyed, breaking his hopes of sailing home to England. Another trope: the wily, manipulative oriental.

marriageable age and should be staying behind in the society of the capital, but she’s adventurous. She’s cultured in Chinese writing and its venerated forms of poetry, and she can go toe-to-toe with anyone in its customary use as word-sport. In her novel, Dalby explores this in her portrayal of a historical visit by a Chinese delegation to Echizen.

marriageable age and should be staying behind in the society of the capital, but she’s adventurous. She’s cultured in Chinese writing and its venerated forms of poetry, and she can go toe-to-toe with anyone in its customary use as word-sport. In her novel, Dalby explores this in her portrayal of a historical visit by a Chinese delegation to Echizen.

It’s most likely here a thousand years ago that Murasaki Shikibu wrote the first part of the Tale of Genji. It’s the site once occupied by the Tsutsumi-chunogon mansion, built by Murusaki’s great-grandfather, Fujiwara Kanesuke. Murasaki was born at Tsutsumi-chonogon and lived much of her life here. Her marriage in 998 was cut short by the death of her husband, Nobutaka, three years later. She moved from here to the court of the Heian imperial palace in about 1005 at the behest of regent, Fujiwara Michinaga, becoming lady-in-waiting to Empress Shoshi.

It’s most likely here a thousand years ago that Murasaki Shikibu wrote the first part of the Tale of Genji. It’s the site once occupied by the Tsutsumi-chunogon mansion, built by Murusaki’s great-grandfather, Fujiwara Kanesuke. Murasaki was born at Tsutsumi-chonogon and lived much of her life here. Her marriage in 998 was cut short by the death of her husband, Nobutaka, three years later. She moved from here to the court of the Heian imperial palace in about 1005 at the behest of regent, Fujiwara Michinaga, becoming lady-in-waiting to Empress Shoshi.

To sit and look over the Genji Garden, established in 1965, is to surrender your thoughts to a life lived on this spot a thousand years ago.

To sit and look over the Genji Garden, established in 1965, is to surrender your thoughts to a life lived on this spot a thousand years ago. death, when she turned her energies cathartically to her Genji monogatari, would she not have put aside her writing brush sometimes and, eyes cast over this very garden in its seasons, have meditated on the transience of life and love? In this earth are there not still traces of her incense, on the wind not faint reverberation of her poems?

death, when she turned her energies cathartically to her Genji monogatari, would she not have put aside her writing brush sometimes and, eyes cast over this very garden in its seasons, have meditated on the transience of life and love? In this earth are there not still traces of her incense, on the wind not faint reverberation of her poems? Lady Murasaki

Lady Murasaki

choosing? Taken by her stories of lustful encounters, and the underlying loneliness and yearning in her own story, I was enamoured with a woman who’d been dead a thousand years. Was she an orientalist ideal I sought in my Japanese wife? Am I another Westerner romanticising the exotic, unable to distinguish the temporal other?

choosing? Taken by her stories of lustful encounters, and the underlying loneliness and yearning in her own story, I was enamoured with a woman who’d been dead a thousand years. Was she an orientalist ideal I sought in my Japanese wife? Am I another Westerner romanticising the exotic, unable to distinguish the temporal other?

shaped stringed instrument, an instrument played by Murasaki’s protagonist, Genji, and Murasaki herself. On a suburban back-street we came across an antique store with battered biwa hanging from the walls and rafters in various states of disrepair. It’s the neighbourhood where, indelibly, I’d exchanged glances with a Maiko more than a dozen years before. Now that I think of it, it was during that visit to Japan that I met my wife, Chizuru.

shaped stringed instrument, an instrument played by Murasaki’s protagonist, Genji, and Murasaki herself. On a suburban back-street we came across an antique store with battered biwa hanging from the walls and rafters in various states of disrepair. It’s the neighbourhood where, indelibly, I’d exchanged glances with a Maiko more than a dozen years before. Now that I think of it, it was during that visit to Japan that I met my wife, Chizuru. Bryce and I cycle down to the site of Miura Anjin’s mansion in Nihonbashi, where there’s a little stone memorial, well-tended. We head over to the imperial palace, and circle the giant statue of fourteenth century samurai,

Bryce and I cycle down to the site of Miura Anjin’s mansion in Nihonbashi, where there’s a little stone memorial, well-tended. We head over to the imperial palace, and circle the giant statue of fourteenth century samurai,  Kusunoki Masashige, on horseback. We pass an oversized motor-scooter with blue flake-metallic paint and chrome to excess. It’s a Harley Davidson parody, incurably Japanese, and its swept back styling oddly mirrors the stance of Masashige’s thundering steed.

Kusunoki Masashige, on horseback. We pass an oversized motor-scooter with blue flake-metallic paint and chrome to excess. It’s a Harley Davidson parody, incurably Japanese, and its swept back styling oddly mirrors the stance of Masashige’s thundering steed.

as their taxi inched along. “We can take a shortcut through Marie Antoinette’s Estate.”

as their taxi inched along. “We can take a shortcut through Marie Antoinette’s Estate.”